Bruno Civolani – The Forgotten Inertia King

- Rus Hinkle

- Jul 30, 2024

- 14 min read

Bruno Civolani is the man responsible for bringing the inertia revolution to the world. While he did not invent the core concepts, he perfected them from Carl Sjogren’s system. Recognition of his contribution to the international firearms industry has been eerily scant, often overshadowed by the companies employing him; Benelli and Breda. There are also very few known public photographs of him. Whether this was by his own will to stay in the shadows, or by the design of another is unknown, but I believe he deserves the rightful recognition for his talents and contributions- the man does not even have a Wikipedia page, instead relegated to just a footnote on Benelli’s page. The following article is the best I have read on Civolani’s biography, written by Victor Andreev. An English version is not readily available, so we have translated the article from native Russian below.

---

When, at the presentation of the Xanthos model in Russia, Breda representative Jean Filippo Adamati said that this gun model was the latest development of the great Bruno Civolani, there was no reaction from the audience, because for most this name is an empty phrase. Few people know about the specific person who is behind the unique design known throughout the world - the Benelli system [more accurately, the Civolani system]. As often happens, the inventor did not reap even a small fraction of the glory of the company that put his creative solution into practice.

Every time the owner of a Benelli pulls the trigger of his gun and a shot is fired, turning on the inertial reloading mechanism, this shot sounds as a salute to the memory of one of the most outstanding weapons designers of the 20th century - Bruno Civolani.

Bruno Civolani was born in 1922 into a peasant family and made his first gun as a boy. To make it, he used materials at hand. Thus, a piece of water pipe turned into a barrel, the breech of which was locked with a homemade butterfly valve of its own design. The gun was loaded with rimfire cartridges. History has not preserved details about whether the point of aim coincided with the point of impact, but the fact that one of Bruno’s shots hit a random passer-by is quite reliable, since there is documentary evidence of this. For the young gunsmith, this story did not end the way he wanted: immediately after the fatal shot, two carabinieri escorted him, like Pinocchio, to the police station. The police did not believe that the boy was able to make a gun on his own, much less hit a passerby with it, so they asked Bruno to shoot again at an improvised target. In general, that time little Bruno managed to escape with a slight fright, but he had to say goodbye to the gun, since the carabinieri told him that, in principle, they could return his “fusee” to the designer, but under one condition: his father had to pick it up from the police station. Needless to say, which of the two options for liberation did little Bruno choose!

The Civolani family lived in the town of San Giorgio di Piano near Bologna. The land that belonged to the family was not very fertile, and when Bruno turned thirteen years old, it was decided to move to the city. In Bologna, the boy was taken as an apprentice to Orlando Grandi's weapons workshop. The owner of the workshop was a good gunsmith. Due to the fact that various weapons repair work was carried out in Grundy's workshop, Bruno had the opportunity to learn in practice the basics of weapons production technology. Subsequently, Civolani always spoke extremely highly of the experience he received from Grandi. It was in this workshop that a meeting took place that predetermined his entire future life. True, this was a meeting not with a person, but with a weapon: Bruno fell into the hands of a gun designed by the Swedish engineer Axel Sjögren. (By the way, last year marked 105 years since the start of serial production of a self-loading shotgun by Swedish engineer Axel Sjögren.) According to Civolani, he was shocked by the idea of using recoil energy to reload a gun, but Sjögren’s implementation of this idea was far from perfect. The unsuccessful experience of the Swedish designer pushed Civolani's imagination.

Civolani liked automatic firearms, the advantages and disadvantages of which he knew absolutely everything about. Bruno was constantly at the skeet, but not because he was interested in the skill of shooters or because he himself was fond of skeet shooting. He observed how guns behaved when fired and thought about how the recoil energy could be used to reload a gun.

Bruno Civolani attended night school, but due to health problems he was never able to graduate. Despite the lack of a school completion certificate, the metal machining skills acquired from the gunsmith Grundy were enough to open the doors of many workshops to him.

At the beginning of the Second World War, Bruno worked as a toolmaker at the large Bolognese metalworking company, Minganti. Because of his love for mechanics, he agreed to be transferred to the town of Palazzolo sull'Oglie (province of Brescia), where the Minganti company had a division. The workshop where Civolani worked was located next to the Manzoli company, which produced weapons and ammunition. After the war, Bruno Civolani founded his own workshop for the production of parts from sheet metal. It was there, while working on the press, that he lost three fingers on his left hand.

The main contribution to the study of the motion of a body by inertia was made by Galileo Galilei, who formulated his “Principle of Inertia”. However, Isaac Newton generalized the conclusions of Galileo and enshrined the concept of inertia in his law. The law of inertia, also called Newton's first law of dynamics, states: “An object at rest remains at rest, and an object in motion remains in motion at constant speed and in a straight line unless acted on by an unbalanced force.”

Civolani began working on an inertia shotgun with the acquisition of a semi-automatic shotgun. After some modification, the inventor installed the inertial bolt he created and began to shoot the gun. A lot of shots were fired. After each, Civolani checked the bolt movement. So he was able to find the parameters of the spring and achieve normal functioning of the bolt group. Bruno Civolani made the springs himself, hardening them, as Civolani’s grandson Andrea later recalled, at home in the kitchen.

It took a long time to experiment, but Civolani showed extraordinary persistence and scrupulousness and ultimately came to the result that he needed. Civolani recalled that at the first shot the mechanism blocked and he had to saw the gun in half. In the end, Civolani ensured that the shutter travel exceeded 80 mm.

The heart of the mechanism is a powerful spring located in the frameof the bolt, which ensures the full cycle of operation of the gun’s automation

The uniqueness of the system proposed by Civolani was that for reloading the weapon, it was not the energy of part of the powder gases or moving parts of the weapon (systems with a long or short barrel stroke) that was used, but the recoil of the weapon as a whole. The automatic operation of Bruno Civolani's shotgun is based on the recoil of a compound bolt with a so-called inertial body. (In fairness, it should be noted that the principle of automatic operation, based on the use of recoil energy of the entire weapon in combination with an inertial bolt and a storage spring, was first implemented in the project of a self-loading shotgun by the Swedish engineer A. Sjögren (from 1904 to 1914). But the similarity of the shotguns Benelli Armi and Sjögren basically end with this. Structurally, they differ in their basis, starting from the locking unit and trigger to their appearance.) The heart of the mechanism is a powerful spring located in the frame of the bolt, which, accumulating energy during the recoil of the weapon, then provides full cycle of automatic gun operation. Thus, the weapon does not contain gas engine parts, its mechanisms become less dirty, the weapon does not require particularly careful maintenance, and the simplicity of the design is the key to its reliability.

It took five years to create a working prototype. Like other natural mechanics who begin to translate an idea straight into metal, bypassing the design stage, Civolani rarely made drawings, preferring to get to the milling or lathe as quickly as possible. He did not change this practice later, working on his subsequent developments. Civolani believed that there was only one way to express your ideas - to prove their value in practice.

In those years, the inventor's family lived in Bologna. Civolani's grandson, Andrea, later said that one of the rooms in the house was dedicated to a mini-workshop, where his grandfather spent a significant part of his time. In the room there was a drawing board, a workbench with a vice and a bunch of files. According to Andrea, Civolani could spend hours telling his family what he was currently working on, and his wife, son and grandson would enthusiastically listen to his stories.

Eventually a working prototype was manufactured, and Civolani, like any other free artists, faced the most pressing question: who to sell his creation to? He appealed to nearly all Italian firearms manufacturers, but was refused everywhere. It is now anyone's guess why leading gun manufacturers, including companies such as Beretta and Franchi, rejected Civolani's proposal. It can be assumed that Civolani's design was not adopted by the major gun manufacturers because they had no desire to produce weapons that would be superior to their self-loading models, operating on the principle of a long barrel stroke or tapping powder gases. Or maybe the matter is completely different: it is likely that the technical equipment of arms factories at that time simply did not allow them to produce firearms that required minimal machining tolerances, and there was no confidence that investments in the acquisition of new equipment would be justified.

Civolani continued to combine work on finishing the gun with making stampings. This stage of his life occurred in the fifties and sixties - a period of economic growth and rapid growth in motorcycle production. Civolani's workshop produced gas caps and throttle grips for a company in the Marche region that produced motorcycles; Benelli.

The history of Benelli begins in 1911. A certain Signora Teresa Boni Benelli, who lived in the city of Pesaro and raised six sons, was tormented by thoughts about what her boys would do in life. It is not known for certain what options came to her mind, but the family’s money was invested in the purchase of metalworking machines. A workshop was built next to the house, and Giuseppe, Giovanni, Francesco, Filippo, Domenico and Antonio, without further ado, named the company Fratelli Benelli SPA. At the very beginning, the brothers were engaged in repairing cars and guns. Then the company began not only to repair motorcycles and mopeds, but also to develop internal combustion engines for mopeds and motorcycles of their own design.

It was racing motorcycles that brought fame to the Fratelli Benelli company, which, in fact, is what the company is famous for now. The Benelli brothers were true pioneers in the development of internal combustion engines in Italy. Their sports motorcycles (since 1923) are regular participants in increasingly popular races. Even before the war, Benelli became one of the most famous motorcycle companies in Italy.

One of the Benelli brothers, Giovanni, was fond of hunting and, back in the 1920s, made a double-barreled hammer gun, and in 1940 he designed a 12-gauge autoloader. The design was based on John Browning's Auto 5, but compared to the Auto 5, Giovanni Benelli's gun had a more advanced trigger mechanism. Innovations in the design of Giovanni Benelli's USM were even protected by four patents. Who knows in what direction the company would have developed if the Second World War had not been raging in Europe at that time: the company was loaded with military orders, whether hunting weapons were available in such conditions.

With the war over, the country returned to peaceful life. The economic boom of the 1950s and 1960s did not spare Italy either. The Benelli Fratelli company developed confidently and firmly occupied its niche among enterprises producing motorcycles.

It was at this time, the designer from Bologna, Bruno Civolani, approached the Benelli brothers. It is likely that he regarded his application to this company as his last chance: after all, Bruno Civolani had already approached nearly all Italian arms manufacturers with his invention, but everything was unsuccessful. It is likely that the Benelli Armi company would never have existed if the Benelli brothers had not believed in the prospects of Civolani’s development.

And yet, why did the Benelli brothers suddenly decide to take a risk and start producing hunting weapons? Some sources emphasize the romantic-emotional aspect: they say that the brothers were passionate hunters and wanted to have a rapid-fire weapon, and in addition, they planned to do a good deed and help an unknown designer. Others, on the contrary, argue that the brothers were guided by a cold calculation: in 1967, the price of a good gun was equal to the price of a motorcycle, but the weight of the motorcycle was about 200 kg (440 lb), while the gun weighed no more than 4 kg (9 lb), and therefore, based on the amount of material spent for the manufacture of these goods, the gun yielded much greater profits. The second version is also supported by the fact that when the European markets were subjected to a massive invasion of Japanese motorcycle manufacturers in the 1970s, in order to save the motorcycle production, (which the Benelli family considered its core business) it was decided to sell the firearms subsidiary. In 1983, the Benelli Armi was sold to Beretta. By the way, the Benelli Fratelli company itself no longer belongs to the Benelli family. But all this would happen later, and in 1967, the Benelli Armi company was created in Urbino, whose products, like the lever of Archimedes, were destined to completely revolutionize ideas about semi-automatic hunting weapons and become a kind of symbol of quality.

As a result of the project, a unique hunting weapon was born, based on the principle of using the inertial force of mass instead of the traditional gas exhaust mechanism. Thus began the production of the Model 121, capable of firing 5 shots in less than one second, even despite some imperfections in the operation of the trigger, which were corrected in subsequent models.

In the first prototypes the recoil energy of light loads was not enough to compress the bolt buffer spring. After all, the kinetic recoil energy of the gun depends on three quantities: the mass of the projectile, the initial velocity of the projectile, and the burning rate of the powder charge. The first samples of Benelli shotguns, when firing cartridges with shot weighing under 32 g and a low initial velocity, were not reliable. They could not function reliably with cartridges more powerful than a semi-magnum. The search for the required values of the stiffness of the buffer spring and the mass of the inertial body of the bolt, as well as refinement of the design of the gun as a whole, gave the desired result: Benelli guns began to easily “digest” both cartridges with a shot mass of 24 g and supermagnums with a shot mass of 55 g. Subsequent models, coming off the factory assembly line, they were capable of firing cartridges loaded with 55 g of steel and 65 g of lead shot.

The first Benelli shotguns were produced only in 12 gauge, and the magazine capacity was 4 or 5 rounds, with a chamber length of 70 mm (2.75in). The standard barrel length with or without a ventilated rib was 70 cm (28in). The fore-end and butt were made of high-quality, carefully processed walnut. The stock drop ranged from 50 to 60 mm.

The barrels for the first Benelli shotgun model were produced in Saint-Etienne (France) at the Manufrance plant using hot forging. The required barrel shape was achieved by forging a tubular blank until it took the shape of the internal mandrel. The bore was then honed and chrome plated.

The first Benelli self-loading shotguns were produced in three versions (Standard, Lusso and Extra Lusso) and had a steel receiver, but very soon they began to use a light alloy for the production of the receiver.

Model 121 marked the beginning of the creation of a new generation of self-loading weapons. This model of gun has long become a legend and occupies a special place in the hearts of hunters and weapon connoisseurs.

The fame of the Bolognese inventor eventually reached even the shores of distant Japan. One of his acquaintances, who had trading partners in Asia, told the Japanese about him, who were not satisfied with the quality of the weapons they produced. The Japanese arrived in Bologna and took Civolani with them to Tokyo, where he worked for a month on a gas-operated gun, since the patent on the inertial reloading system had not yet expired.

The inventor's family spent only the winter months in Bologna. In the early 70s, Civolani built a house in the Apennines, between Bologna and Florence. In the house, surrounded by greenery, Civolani lived in the summer. His workshop was also located there. Every summer, for a long period, machines were delivered to the mountains by truck, and work continued there. Bruno was very protective of his projects. Drawings were made only at the moment when he was working on the shape of the gun. Then he produced an already operational prototype, which only had to be put into production.

On September 25, 1997, Bruno's favorite brainchild - a gun - took his son away from him. An accident occurred that resulted in the death of Mauro Civolani. Bruno did not recover from this tragedy until the end of his life. For two years after the death of his son, the inventor did not take up arms. Fortunately, his family was with him at this time, especially his grandchildren Andrea and Stefania. Everyone understood that designing weapons was the meaning of his whole life, and soon Civolani Sr. was still able to return to work.

In 1999, Bruno introduced a new reloading system with a gas release mechanism. The principle of operation of the mechanism is based on the tapping of powder gases from the barrel bore into two gas cylinders symmetrically located under the barrel. At first, this mechanism was installed on a hunting rifle, but real success came when the Benelli M4 Super 90 shotgun, equipped with a new type of reloading mechanism, was adopted by the US Army as a combat weapon. Then almost all the newspapers in the world wrote about Civolani.

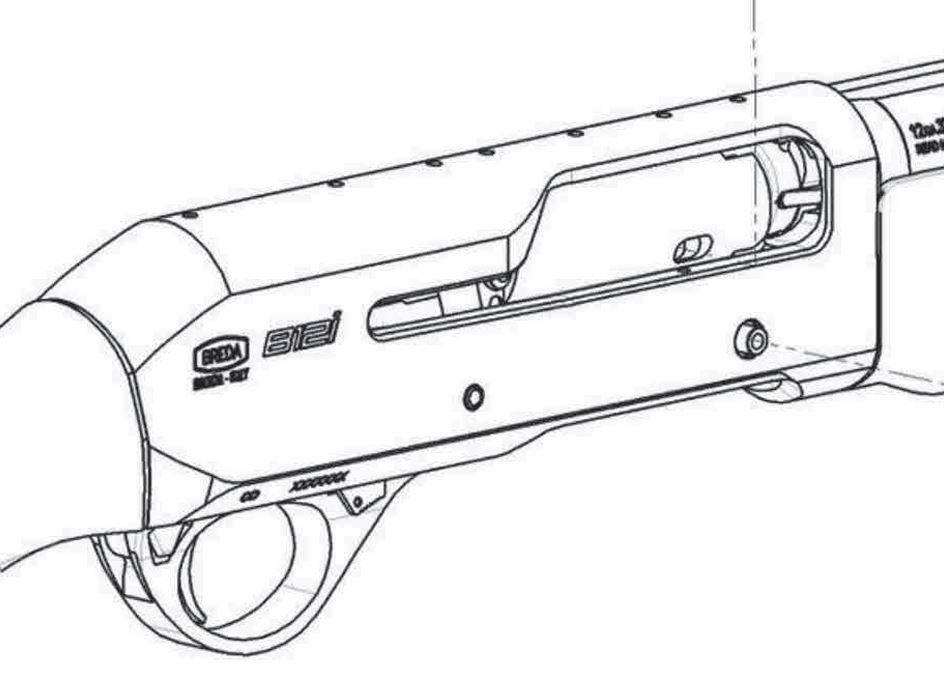

At 84, the inventor designed the Xanthos 12-gauge semi-automatic shotgun for Breda. Although, more precisely, the Breda company entered into a contract with Bruno Civolani to use two of his patents (locking bolt and feed system) in the design of the Xanthos model, with the obligatory participation of the designer in the creation of the prototype and subsequent design supervision.

The operation is based on the inertial principle, but with a patented innovative locking system. The Xanthos proprietary action differs from the Benelli system. The main difference is that the bolt is locked by a cylinder that moves in a vertical plane and fits into the corresponding recess in the barrel extension, and not by a rotary bolt. Otherwise, the principle of operation of the inertial system is simple and understandable: when fired, under the influence of recoil, the bolt carrier is shifted forward and a powerful spring located between the bolt carrier and the bolt is compressed, which then, when released, throws the bolt carrier back, as a result of which the entire reloading cycle of the weapon occurs.

Also noteworthy is the thin-walled steel receiver, stamped from a tubular blank (Civolani made a steel receiver for the gun, thereby building a bridge to his past as a stamper). There are simply no analogues in terms of manufacturability among smooth-bore semi-automatic machines of the classical layout. The receiver turned out to be extremely light and at the same time rigid, which had the most positive effect on the weight of the gun as a whole and the elegance of its appearance.

Participation in the work on the new Breda model did not add worldly fame to Bruno Civolani. The name of the designer still remained little known to the general public. We only have to guess whether Bruno Civolani was looking for recognition and fame or running away from them, because only he himself could answer this question, but, alas, we will no longer receive an answer to this question from him, just as new models of weapons will not appear, in the creation of which Bruno Civolani took part.

Victor AndreevPhoto from the author’s archive OKHOTNICHIY DVOR NO. 8 (AUGUST) 2010

Original article: https://shooting-iron.ru/publ/10-1-0-1489

Addendum by Rus Hinkle

This addendum is to add more information to Mr. Andreev’s fantastic biography on Civolani. In 1967 when Benelli Armi was established, Benelli did not have immediate capability to manufacture firearms. Benelli Armi was formed as a joint company between Fratelli Benelli motorcycle company and Breda, with each company owning a 50% stake. Breda would handle a majority of the manufacturing while Benelli operated primarily as sales and assembly. In 1983 when Fratelli Benelli sold Benelli Armi to Beretta, Breda retained a 25% stake and continued primary manufacturing of the Benelli line. This would continue until 1999 when Breda fully divested from Benelli to focus on Italian military contracts. By 2000, Benelli Armi was a wholly-owned subsidiary of Beretta, and both companies now performed Benelli's manufacturing.

It is unknown if Bruno Civolani approached Breda when he was selling his design. Breda at the time was manufacturing very high quality long recoil shotguns, but their specific small arms division is very small compared to the rest of the company. Breda was primarily known as a manufacturer for mass-transit vehicles (trains, trolleys, busses, aircraft, etc.), and their small arms division has always been relatively small since the division’s establishment in the early 1910s. Fratelli Benelli would eventually be bought out in 2005 by Qianjiang Motorcycle Group. In 2006, Bruno Civolani’s patents expired. Bruno Civolani passed away at age 86 in 2008. Breda, still having retained the entire technical package from when they previously manufactured Benellies for thirty years, was able to freely resume production of the “classic” Benelli lineup, now with superior deep-bore barrel technology.

Hello Rus, I just read the article about Bruno Civolani. I would like to thank you very much for writing and remembering him. Really many thanks!

I personally supported my grandfather in the development of the Breda Xanthos. If you have any question, feel free to ask me; I'll be happy of this.

Best regards

Andrea Civolani